Call me by my name – reflections on names, identity and teacher development

As a teenager, I had a teacher who ‘translated’ our names into English. João would become John, Mariana would be Mary and other questionable, less obvious, choices also took place. Mind you, this was a substitute teacher, so we perhaps had two or three lessons with her. As much as I’ve never truly embraced my name, being called James felt very uncomfortable.

Years later as a teacher, I had unconsciously vowed never to change my students’ names, unless that was something they asked me to. Joãos would be Joãos and Marias, well, Marias. When speaking fast, I sometimes transfer some sounds to something that is closer to English; so, if you are a Carlos, I might use the typical retroflex r from English, something which I don’t normally use in my first language, to address you.

Even though this happens considerably less often in Brazil than in Asian countries, for instance, naming students something else has ‘the power to exclude, stereotype or disadvantage students’ (Peterson et al., 2015). Our name is the first piece of identity that is imposed on us. It usually contains information about us such as the gender we were assigned at birth, nationality and even cultural information. Names carry weight and their choices are usually informed by things that go beyond simple likes and dislikes.

Take for instance the name Matteo, which became increasingly popular in the late 90s because of the telenovela Terra Nostra. Matteo Batistela was a white, green-eyed Italian immigrant, who was separated from his lover, Giuliana. Unsurprisingly, name popularity in Brazil can be connected with the success of telenovelas.

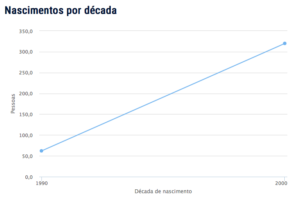

Number of people named ‘Matteo’ around 1990-2000.

Source: IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)

https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/nomes/#/search/response/713

On the other hand, in 1996, the telenovela Chica da Silva was very successful, but the protagonist’s name Francisca, did not gain popularity. On the contrary, fewer and fewer people were given that name in the 90s.

Number of people named ‘Francisca’ from 1910-2000.

Source: IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)

https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/nomes/#/search/response/937

Chica da Silva was about a slave who becomes a free woman. Chica was a black woman whose relationship with a white man was not recognized, she was his concubine. Chica was also a sassy, sharp-tongued and a very sexual woman. Those were probably not traits parents wanted their daughters to be associated with.

The name I was given at birth had a peak in the 1980s. It is not associated with anything bad or undesirable, yet I never felt comfortable with it. It being a very popular name, I was normally called by my surname, Veigga, or other nicknames: Thi, Thithi, Thithis, Tom, Mel, Tico… As I got older, I thought I would start owning my name at some point, but it never really happened. I eventually decided that I was going to have it changed.

I decided that I was no longer going to endure being called something I dislike just because my mother, with the best intentions, chose to name me this. I made the decision not to justify myself anymore whenever I asked people to call me T. because I did not like my name. It took me many years to understand I do not owe anyone explanations about my likes and dislikes. My feelings and my discomfort are valid and they do not need to be validated nor questioned by society. Deciding to change my name was part of a process in which I had to acknowledge how important it was for the construction of my identity, something I had taken for granted for many years.

The moment I decided to use Taylor as my name, I realized how it was important to my identity. The process of changing it made me reflect on a myriad of other issues. What is the impact on students’ identity of naming them something else for the sake of keeping using English in class? What does a name actually mean about someone? What about my teacher identity? Will it also change now that, in the eyes of society, I am a different person? How is this change going to affect my relationship with my current students? What about future students? Will it change the way the market sees me? Did my choice of a more Anglo Saxon spelling for my name instead of the more Portuguese like Teilor mean that I would always be trapped in the colonial clutches of my upbringing? I do not have an answer to most of these questions yet.

What I learned recently is that identity as a language teacher is crucial for professional development (Burns and Bell 2011; Lee 2013; Tsui 2007 cited in Cheung, 2015). Once we start teaching, there is a shift in our identity and those shifts may continue to happen throughout our career due to our interactions within schools and broader communities (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009). As someone who is involved in teacher education programs, changing my name and reflecting on the shifts of my identity made me question ‘what we might need to learn about teacher identity from the literature to better design our own teacher education programs’ (Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009: 176). One of the trickiest parts is to first understand identity in its complexity.

One thing literature about teaching and teacher education reveal is that identity is dynamic. As I mentioned before, a teacher’s identity shifts under the influence of many factors, such as emotion and job and life experiences. Identity is not fixed, but rather negotiated through experience and the sense that is made from that experience (Sachs, 2005; cited in Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009). Sachs’ view of teacher identity encompasses both personal and professional aspects. These would help teacher construct the way they are, act and understand their work and place in society.

While in initial teacher training courses we talk about professionalism, we do not give emphasis on identity. Hammerness, Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2005) highlight the importance of tackling this issue:

Developing an identity as a teacher is an important part of securing teachers’ commitment to their work and adherence to professional norms… the identities teachers develop shape their dispositions, where they place their effort, whether and how they seek out professional development opportunities, and what obligations they see as intrinsic to their role. (Hammerness, Darling-Hammond, & Bransford, 2005, pp. 383–384)

This made me reflect on how important aspects of my teacher identity were developed rather late and how I believe I would have benefited from having this sense of awareness early in my career. I tend to agree with Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) about the need to incorporate what we know about contexts and communities and how these influence the way teachers develop their teacher identities positively, especially teachers in their early years.

To wrap it up, when we start being called teachers by other people, something in our identity changes, just like mine changed the moment I adopted the name Taylor. Some say that when we learn foreign languages, the way we express ourselves in those languages changes; therefore, our identities change. Perhaps it is time we thought more about not only ourselves and the construction of these identities, but also about our students’, as they learn a new language.

References:

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189.doi:10.1080/03057640902902252

Cheung (Nanyang Technological University), Yin Ling & Ben Said, Selim & Park, Kwanghyun. (2015). Advances and Current Trends in Language Teacher Identity Research. 10.4324/9781315775135.

Peterson, B., Gunn, A., Brice, A., & Alley, K. (2015). Exploring names and identity through multicultural literature in K-8 classrooms. Multicultural Perspectives, 17(1), 39-45. doi:10.1080/15210960.2015.994434